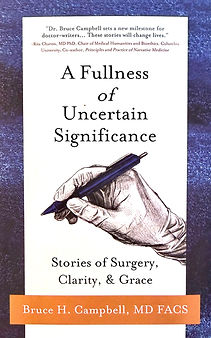

- Bruce Campbell MD

- Jun 12, 2019

- 3 min read

Twenty years from now you will be more disappointed by the things you didn’t do than by the ones you did do. So throw off the bowlines. Sail away from the safe harbor. Catch the trade winds in your sails.

- Mark Twain

Head and Neck cancer surgeons know when “The Questions” are coming. A casual conversation eventually turns to “What do you do for a career?” The pleasant exchange is replaced with talk of disfigurement and life-threatening illness. The person’s brow furrows. “How can you deal with that day after day? Isn’t it depressing? Why didn’t you pick something happier for a career?”

These are legitimate questions. As a medical student many years ago, I enjoyed every rotation and wondered how I would ever narrow down my choices and pick a specialty. Eventually, I decided that I was most content in the operating room. Even when I knew I would become a surgeon, there were still dozens of trajectories which my career might have taken.

One day in 1980, as a 25-year-old senior medical student, I was in a departmental conference, listening to a visiting out-of-town cancer surgeon. He ran through his slide show, describing a procedure he had devised to restore voice for patients who had undergone removal of their voice boxes. It was a complex operation that involved the creation of tubes of lining tissues that shunted air from the trachea to the back of the throat that could then exit through the mouth, thus allowing the person to speak.

It was interesting, but at my level of training, I was confused by approach and the diagrams. I was years away from doing any type of surgery on my own. At some point during his talk, I probably checked my watch, wondering when the conference would be over.

Then, the visiting surgeon flipped the controls and adjusted the volume on a 16-mm movie projector. The light flickered as the film moved past the bulb. There, on the screen, was a man who had undergone a total removal of his voice box. The surgeon asked him a question, and the patient responded by holding a vibrating device against his neck to create an artificial, machine-like sound that he shaped into words. He was understandable, but his voice sounded synthetic.

The next scene showed the same patient after he had undergone the voice-restoring procedure. This time, he answered questions by bringing his hand up to his neck and covering his stoma to redirect air from his lungs through the shunt and into his throat. He was able to talk! The sound was natural and fluent.

I was enthralled by his ability to speak and by his big smile at the end of the movie. Once the presentation was complete, the senior surgeons asked technical questions about the operation and whether it might cause more problems than it solved. I, on the other hand, was amazed. All I could think was, “I want to do something like that!”

Although the procedure described by the visiting surgeon never caught on (there are much simpler techniques today), that movie steered me toward a career devoted to patients with head and neck cancer. I can trace the rest of my life to that day. A few weeks later, I was humbled when a cancer patient’s family included me in their circle while making difficult end-of-life decisions. That sealed it.

I have loved my work even on the many days I when I have found it overwhelming. When someone asks me my story, I tell them about that lecture. I describe the movie and the man’s huge grin. Over the decades, I have been privileged to see similar grins on my own patients. It has, indeed, all been worthwhile.